Semantic Segmentation of Underwater Scenery

Introduction

Over the past four months, I have been working on an extensive project entirely on my own, which I am thrilled to present in this blog post. The focus is semantic segmentation of underwater scenery, which involves the delineation of various semantic elements within diving photographs, such as fish, corals, vegetation, rocks, divers, and wrecks.

Inspired by the 2020 paper "Semantic Segmentation of Underwater Imagery," I began by carefully cleaning and correcting the publicly available dataset from this research. Recognising the need for a more robust and diverse dataset, I extended it with new images from my own diving trips, investing significant effort to manually annotate them in detail. I published this enhanced dataset at Kaggle.

To tackle the task of underwater semantic segmentation, I employed both classical deep learning architectures used by the original paper and cutting-edge vision transformer architectures. I trained six different large models, and I am pleased to report that one of the models surpasses the benchmark results established by the original paper. Here is a demo video of the best model I trained:

Join me as I delve into the details of this project.

Dataset and Task

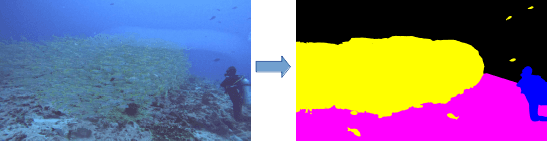

In essence, the task involves assigning a class to each pixel in an input image.

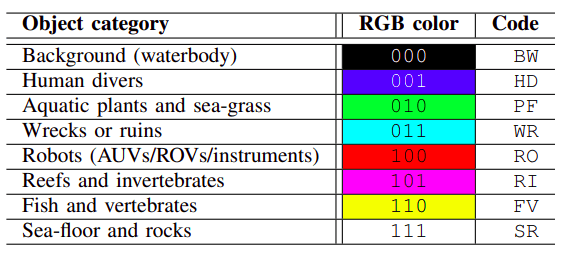

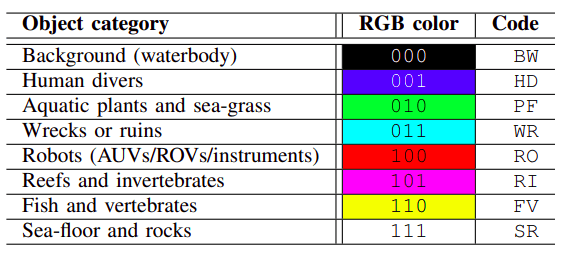

The eight classes defined in the original paper, which I have adhered to, are:

The underwater nature of these images introduces a host of unique challenges:

- Variable Visibility: Water composition and weather conditions significantly impact visibility. Depth also plays a critical role, as colors, especially reds, fade the deeper you go.

Demonstration of color degradation at different depths - Source

Demonstration of color degradation at different depths - Source

- Diverse Natural Landscapes: Aquatic environments vary dramatically by geographic location. A good model must learn high-level concepts, such as the general appearance of fish, as it is impractical to provide training samples for all existing species.

This chart showcases common species in French Polynesia, from Franko Maps. Notice the wide variety of shapes, colors and patterns. It would be impossible to provide training data for all existing species.

This chart showcases common species in French Polynesia, from Franko Maps. Notice the wide variety of shapes, colors and patterns. It would be impossible to provide training data for all existing species.

- Complex Scenery: Underwater landscapes can be difficult to interpret even for humans. Many species have evolved to blend seamlessly with their surroundings.

💡 Why is this task relevant? Scene understanding is crucial for autonomous underwater robots. By comprehending their surroundings, these robots can navigate more effectively, identify and monitor marine life, map underwater environments, and carry out complex tasks such as inspecting underwater structures or assisting in search and rescue operations.

In order to solve this task, we cast this problem as a supervised learning semantic segmentation task. The authors of the original paper published a dataset of approximately 1600 labelled images, which I have corrected and extended using photographs of my own diving trips.

Let's look at a few of the new images that I introduced to the dataset, and discuss the challenges they pose in the semantic segmentation task:

A cute anemonefish hiding in an anemone. A good model should be able to understand that the fish belongs to the

A cute anemonefish hiding in an anemone. A good model should be able to understand that the fish belongs to the fish class whereas the anemone is an invertebrate.

A porcupinefish hiding in the shadows, easily overlooked.

A porcupinefish hiding in the shadows, easily overlooked.

A complex underwater scene involving

A complex underwater scene involving aquatic plants, fish, sea floor, reefs and bodywater classes. A good model has the challenge to understand the many actors involved in this scene.

A sea turtle at 30 meters depth. The loss of color at great depths is very noticeable in this picture. A good model should be able to handle color degradation.

A sea turtle at 30 meters depth. The loss of color at great depths is very noticeable in this picture. A good model should be able to handle color degradation.

In order to enhance the pre-existing dataset, I took the following actions:

- Identified 86 masks in the original training set that needed corrections, and re-annotated them from scratch.

- Selected 166 images from my own diving trips and manually annotated their segmentation masks.

The resulting dataset has exactly 1801 annotated images, which I published in Kaggle. Annotating data was a very humbling experience for me, since I used to underestimate how time consuming and complex it can be. I wrote a separate blogpost tutorial explaining how the tools I used, as well as a few insights and tricks.

Experimental setup

I had two goals in mind when I undertook this project. Firstly, reproducing the results from the original paper. Secondly, trying to improve their results by using my new extended dataset and leveraging cutting-edge architectures like vision transformers.

I therefore selected three CNN architectures as well as a vision transformer architecture for my experiments:

| Model | Backbone | Crop size | Number of parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| DeepLabv3+ | ResNet50 | 512 x 1024 | 43.581 M |

| PSPNet | ResNet50 | 512 x 1024 | 48.967 M |

| UperNet | ResNet101 | 512 x 512 | 85.398 M |

| Swin ViT | not applicable | 512 x 512 | up to 195.520 M |

| Architectures that I used in this project |

I leveraged the toolbox MMSegmentation (check out my tutorial on this blogpost!), which already provides high quality implementations of the architectures I mentioned. Adjusting the codebase for the underwater segmentation task only required a few additions to the code, which are available in my Github. Pre-trained weights (from ImageNet) were used for all models.

The original paper reports results on similar architectures, which I will use as a baseline to compare the performance of my model.

| Model | Backbone | Resolution | Number of parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| DeepLabv3 | unspecified | 320x320 | 41.254 M |

| PSPNet | MobileNet | 384x384 | 63.967 M |

| SUIM-Net | VGG | 320x256 | 12.219 M |

| From table III of the SUIM paper. SUIM-Net is an original architecture proposed by the authors, which achieved the best results on their paper. |

Experiment results

Results of the original paper (Baseline)

Recall the list of classes defined by the original authors:

The authors of the original SUIM paper reported results only for classes HD, WR, FV, RI and RO:

The authors of the original SUIM paper reported results only for classes HD, WR, FV, RI and RO:

| Model | HD | WR | FV | RI | RO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSPNet | 75.76 | 86.82 | 74.67 | 85.16 | 72.66 |

| DeepLab v3 | 80.78 | 85.17 | 79.62 | 83.96 | 66.03 |

| SUIMNet | 85.09 | 89.90 | 83.78 | 89.51 | 72.49 |

| IoU of five classes, as reported in table II of the original paper. |

Replication of the results of the original paper

I trained three models using the exact same dataset that they used, in order to replicate their results. I decided to report stats on all eight classes, although the original authors only reported results for the first five classes:

| Model | HD | WR | FV | RI | RO | SR | VG | BG | mIoU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSPNet | 85.39 | 73.13 | 75.08 | 73.11 | 73.32 | 67.62 | 12.11 | 88.87 | 68.59 |

| DeepLabv3+ | 86.33 | 69.48 | 76.79 | 72.46 | 81.91 | 65.68 | 12.06 | 88.68 | 69.17 |

| UperNet | 86.18 | 72.2 | 77.53 | 70.35 | 81.88 | 66.39 | 6.73 | 88.61 | 68.73 |

💡 Interpretation of results: If we make a pairwise comparison between the original paper results and my own replication, looks like my models are significantly better at segmenting HD, RO and FV ; whereas their models do better in the under-represented class WR, and in the umbrella class RI. I believe the divergence is due to the fact that they seem to have merged classes RI and SR for training, and also because of the different backbones and hyperparameters choices.

New architectures and extra data

After replicating the results of the original paper, my next goal was to try to surpass them by:

- Adding 181 extra images to the training dataset, collected and annotated by myself.

- Trying vision transformer based architectures, which have proven very successful in many computer vision tasks in recent years.

The results are summarised in the following table:

| Model | HD | WR | FV | RI | RO | SR | VG | BG | mIoU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSPNet | 85.28 | 74.8 | 76.34 | 74.49 | 81.35 | 68.24 | 8.77 | 88.96 | 69.78 |

| DeepLab v3+ | 86.06 | 72.55 | 75.18 | 71.28 | 77.93 | 65.23 | 13.35 | 88.2 | 69.72 |

| UperNet | 85.85 | 70.39 | 78.9 | 73.36 | 84.57 | 65.41 | 10.5 | 88.53 | 69.69 |

| Swin ViT | 84.47 | 71.2 | 85.46 | 72.35 | 86.27 | 67.2 | 9.63 | 88.56 | 71.14 |

💡 Interpretation of results: The extra data gives all models a boost of ~1 point of mIoU. Moreover, the SWIN ViT is able to surpass all CNN-based architectures by an extra ~1.5 mIoU.

Training loss of Swin ViT. The loss function decreases quickly in the first 20k iterations, and gradually plateaus.

Training loss of Swin ViT. The loss function decreases quickly in the first 20k iterations, and gradually plateaus.

Optimizing ViT hyperparameters

After observing that the Swin ViT had a high potential, I spent quite a lot of time further tuning the hyperparameters of the model.

The swin transformer architecture. The number of swin transformer blocks at each stage, number of channels at each stage and the window size are hyperparameters of the architecture.

The swin transformer architecture. The number of swin transformer blocks at each stage, number of channels at each stage and the window size are hyperparameters of the architecture.

First, I tried increasing the size of the model. More complex models were able of raise the validation IoU:

| Depth at each stage | Number of heads | Number of channels in decode head | window size | embedding dimension | number of parameters | mIoU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2, 2, 6, 2 | 3, 6, 12, 24 | 96, 192, 384, 768 | 7 | 96 | 27.520 M | 70.5 |

| 2, 2, 18, 2 | 4, 8, 16, 32 | 128, 256, 512, 1024 | 12 | 128 | 86.880 M | 71.14 |

| 2, 2, 18, 2 | 6, 12, 24, 48 | 192, 384, 768, 1536 | 7 | 224 | 195.201 M | 71.79 |

| 2, 2, 18, 2 | 6, 12, 24, 48 | 192, 384, 768, 1536 | 12 | 224 | 195.520 M | 73.17 |

Secondly, I tried out a range of learning rates. The default one produced better results than any of the alternatives I tried out.

| learning rate | mIoU |

|---|---|

| 63-e | 20.55 |

| 6e-4 | 69.46 |

| 6e-5 (default) | 73.17 |

| 6e-6 | 2.12 |

💡 increasing the model complexity boosted mIoU further by 2 points!

Demo: Inference over diving videos

To showcase the performance of the best model and also its limitations, I hand picked a couple of clips from my last diving vacation and used the best trained model to perform inferences over each frame.

Let's have a look at the results:

A playful dolphin during a dive in Rangiroa - The segmentation is quite decent taking into account that there is just a single dolphin in the entire training dataset. The model manages to identify the dolphin as "fish and vertebrate" when the camera captures its entire body, but it struggles to differentiate it from the diver when the dolphin is partially occluded.

A snorkelling session in Bora Bora, showcasing a huge school of black-tip sharks, stingrays, as well as humans snorkelling (me!) and smaller fish. This hectic scene poses a generalization challenge for the model, which is trained in less populated scenarios and hasn't seen any humans snorkelling. Yet, the segmentations are quite resonable, showing great generalization power to unseen scenarios. Notice the sea floor segmentation often flickering between reef and sea-floor and rocks classes.

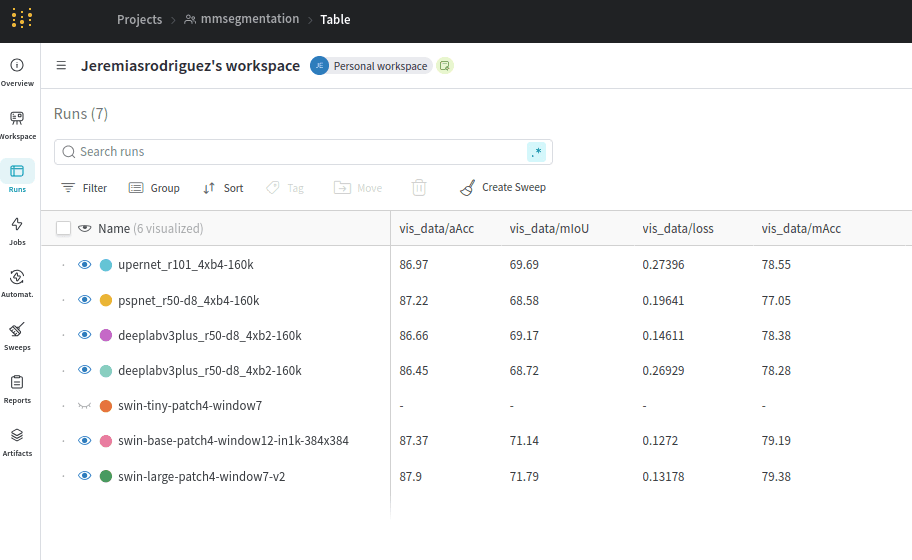

Tracking experiments with W&B

I used Weights&Biases to track the different experiments and quickly compare key stats like mIoU

You can inspect pretty much any details of interest of your runs, from stats to actual predictions. For instance, here we can see how the prediction of a given validation sample changes as the number of iterations increases:

Segment Anything 2 (SAM2)

For the sake of comparison, I ran SAM2 on the dolphin video shown in the intro. To be more specific, I used the SAM2AutomaticMaskGenerator model with default parameters.

Summary of contributions and future work

In this project, I tackled the task of underwater semantic segmentation. I began by replicating the results of the 2020 paper "Semantic Segmentation of Underwater Imagery," successfully training three CNN-based models that achieved IoU values comparable to those reported by the paper.

I then extended the public dataset by adding 181 original images and annotations. Training the same models on the extended dataset resulted in an increase of about 1 point in mIoU. Additionally, I trained a modern SWIN ViT architecture, which was developed after the original paper was written. Using ViT led to a further increase of 2 points in mIoU.

Overall, the segmentations are very reasonable, as demonstrated in the demo videos. It is important to note that the dataset used is quite small by modern deep learning standards, containing only 2000 samples. Despite this, the trained models are able to produce sensible segmentations, which would be bound to get better if more annotated data was made available.

One challenge encountered was distinguishing between Sea floor and Rocks and Reefs and Invertebrates, with the models often oscillating between these classes. The authors of the original paper seemed to have merged these classes under the hood, and my experiments could benefit from a similar approach, as they are often indistinguishable and mislead the training process.

The models also struggled to produce precise boundaries for divers and fish that blend with their surroundings. This may be due to imprecise annotations in the dataset and the small size of the training dataset.

To sum up, I am proud of the models' ability to identify varying species of fish and human divers, which are two of the most interesting and interactive classes for potential applications. I enjoyed refining my computer vision skills, and I hope the public dataset continues to grow.